1. Reforms are making a major impact (more so than changes in US relations)

Reforms have made a marked impact on the life of daily Cubanos, with presumable shifts in the island’s socialist core. The legitimization of 170+ private businesses in 2011 means that hair dressers, driving instructors, bathroom attendants, and even magicians are now present in higher rates than before. A restaurant owner in Havana, who pursed his dream to open up one of the first private restaurants in the city in the mid-1990s, explained how at the beginning the government viewed him suspiciously, like he was doing something wrong, and sent a steady stream of inspectors to fine him for the slightest of violations. In contrast nearly twenty years later, the environment has vastly improved to the point where the government now views his occupation positively, even allowing access to small amounts of credit for such entrepreneurs for the first time last year. As he said, “some people just want to work a job, while others are entrepreneurs – now those that fall into the latter category are able to pursue their path.” This official experiment with capitalism has been a major driver of change on the island, and may even outstrip what an end to the US embargo would mean.

The ability to sell (or exchange) your home – a recent option for Cubans

This guy can’t have more than four years of (official) experience . . . I usually don’t settle for barbers with less than nine (made an exception).

2. Private enterprise is more efficient, but that doesn’t mean it’s always the answer (although I am now also more of an ardent capitalist). In addition, while capitalism is slowly taking root, its not quite there . .

The efficiency of private enterprise over state-run entities is difficult to argue against, and I found myself more ardently in favor of capitalism (within reason) after the visit. A short narrative explains my stance. Going to the Viazul (state-run tourist bus) station a day before to get tickets to a town three hours away, I was greeted by a long line (very typical) extending well outside the building. Taking my place at the end, I was resigned to wasting over an hour here, only for the ticket vendor to likely inform me the bus was sold out. At about the same time, a private taxi owner (likely allowed as part of reforms in the past few years) came by soliciting passengers for his vehicle, offering rides to the same destination. Charging $15 rather than the $12 for the state-run bus, the extra funds would result in getting picked up from my house, getting dropped off at my house in the next town, and a faster ride with just three other passengers (and even more space, given that the double backseat rows of the car fit five). In addition, he was present and immediately available, with a line of other private taxi owners outside, to meet the excess demand in a manner that the state could not. Thus I could either wait in line for an hour or longer and take a less convenient ride, or spend slightly more for a higher level of service and not have to wait at all. The choice was clear, and the contrast behind the efficiency of the private enterprise and the failings of the state could not have been any clearer.

Not to say “our” system is infinitely better. The pursuit of endless profits at all costs drives innovation and progress, but has downsides in creating an elite corporate class that wields an inordinate level of influence (sounds like I could be Bernie’s campaign manager). In contrast, despite the experimentation with capitalism in Cuba, it clearly hasn’t taken full root. At a baseball game, the crowd around me began discussing in earnest the situation of a Cuban player who left to go play (in Venezuela?), drawing a much healthier salary. Rather than appreciate or understand such a move, the crowd reaction was more one of universal derision, making fun of him for becoming, for lack of a better term, a ‘fancy pants.’ Later that night at a small restaurant frequented by tourists, all the tables were full, although two (including yours truly) were in the process of paying the bill. When another couple came in to get seated, the restaurant employee explained there was no space. Seemingly content with the level of business for the evening, she simply turned the potential clients away, rather than ask them to wait for a few minutes. Aghast at potential loss of profits, the other table of tourists from a capitalist country that were paying the bill, told the newcomers to wait and they’ll give them their table in a few minutes. Seeing other clients approaching the packed restaurant I tried to do the same, asking for the bill so I could get out of her way and not impede additional profit making that evening. Of little concern to her, I got the bill over twenty minutes later after asking two more times, during which many a potential new customers were forced to look elsewhere. Capitalism clearly exists in forms, just the lesson on maximize profits at all costs perhaps hasn’t taken root.

A mall in Havana at X-mas – the future of Cuba?

3. Rules are supreme, but people find ways around them

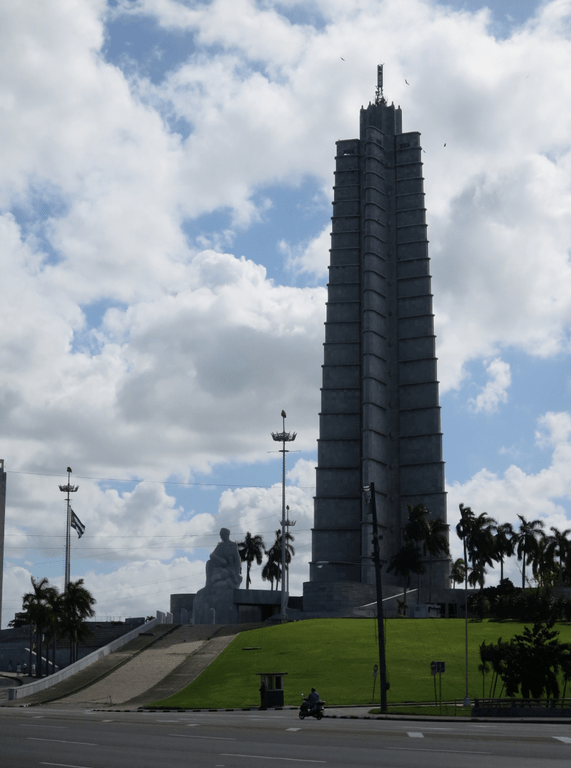

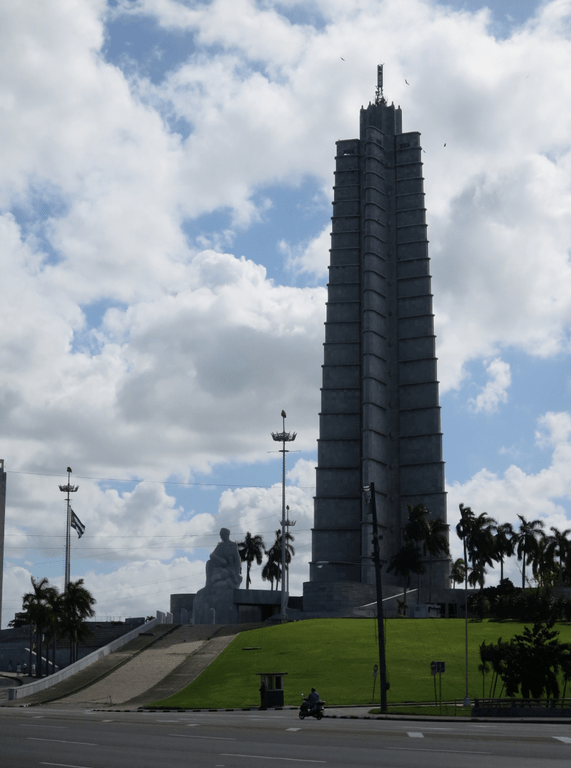

Cuba can extremely be bureaucratic at times, with rules heavily enforced down to seemingly minor levels. I realized this early on, when a whistle happy guard nearly blew out my eardrum merely for looking at the José Martí monument while it was ‘closed.’ At other times, it seems odd when you go into a ice cream shop there is a limit on the number of items you can purchase. A maximum of four scoops – how decidedly un-American!

I got in trouble just for looking at this?

Fear of being caught outside the bounds of the rules is high – this was played out when a set of casa owners demanded I register with them instantly upon arrival, lest a random inspector happened to drop in during the time I went to the bathroom. At the same time, other casa owners never me registered at all, indicating that the perils of being caught may at times be outweighed by the benefits of off-the-books transactions.

At any rate, decades of arcane regulation have engendered resilient island. To illustrate – after waiting over thirty minutes in line for churros at a weekly Saturday night festival (did I mention things move slowly?), my quest was nearly derailed when the vendor stated that everyone who wished to purchase churros must have a child with them (I had only been waiting in line for 30 minutes instead of nine months by the time he made the announcement, so I couldn’t have done much about it anyways). Apparently despite the many adults present, the sale of churros was only for children. There was a big loophole, however, in that each child was allowed to purchase up to five sets of churros, thus allowing them to share with any adults that may have been funding diabetes-inducing nighttime snack.

Essentially defeated by a system I didn’t understand, I was saved at the last minute by the intervention of a young girl, who instantly grabbed my money and explained I was in line with her. Before I could even realize what was happening, the unimpressed vendor relented, and allowed us to buy the maximum between us. Bureaucratic rules up against the creative resilience of a twelve-year old with nearly a decade’s worth of experience navigating the system. The latter won out, as I suspect it does the majority of the time.

4. Poverty and class differences exist

When you think about Cuba, you think of an idyllic socialist paradise where all are equal and no one looks down on anyone else, no? While the contrast between the haves and have-nots may not be as dramatic as in many of its neighbors, poverty and class differences are surprisingly ingrained in society, despite decades of policies to eliminate both. In fact, they may even be getting worse.

A simple 10-minute walk between rundown, old dwellings of downtown Cienfuegos, and the recently renovated mansions and private clubs of its coastal Punta Gorda neighborhood reveals unexpected stark differences. Or perhaps the presence of beggars on the streets of Havana will stand out. The sheer desperation of an elderly campensino so eager for financial renumeration in Vinales that he tracked me down on his horse three times during an obvious twenty minute hike to me show the way (for a dollar), also came as a bit of a shock.

Upper class goats slumming it at a public housing complex

The private club where they (the goats) usually hang

Such differences have become further entrenched through the use of dual currencies – the Cuban Convertible Pesos (CUC) and the Cuban Pesos (or moneda nacional). CUCs are traded evenly with the dollar and primarily utilized by tourists, thus flowing into the pockets of those working in the tourist industry. Moneda nacional on the other hand (which is traded at a rate of 24 to one CUC), is the ‘local’ currency used to buy heavily subsidized items. Middle class residents who are able to rent out their rooms to travelers gain access to a steady stream of CUCs, further distancing themselves from those who deal solely in moneda.

A former doctor in Holguin exemplified this dynamic – she left the medical profession and her 50 CUC equivalent salary each month, to run a bed & breakfast where she can earn 25 CUC per evening, equaling her previous salary is just two nights. An internal sort of brain drain when the earnings of a B&B host vastly outstrip that of a respected doctor, who at the same time is now able to distance herself from her former state-paid colleagues. The result is a new class of enriched, tourism-dependent entrepreneurs, who enjoy steady access to cold hard beautiful CUC cash.

5. Old cars are nice, but also a reminder that environmental regulations make a big difference

The iconic American cars dating back from 1950s cruising down Havana’s Malecon contribute to the nostalgic vision of Cuba as a place stunted in time, reminiscent of an earlier, simpler era. The cars themselves seem to define Cuba in a nutshell – a visible reminder of the US embargo, while the fact that they still run is a testament to local ingenuity.

While the cars do make for a beautiful backdrop, most of the restored ones have been done so solely for the purposes of generating a tourist buck (CUC) or two. In fact, one cab driver mentioned how the older cars were in the process of becoming more expensive than importing newer ones from non-US manufacturers, given the insatiable tourist demand for a trip down memory lane.

Nonetheless, the less publicized side of this anachronism is the high rates of diesel fumes inhaled. Walking down a street in Havana, described as a ‘diesel sauna’ by a fellow traveler, is a pleasant experience, until one of those cars rolls by emitting who knows how many CO2 emissions in the form of plumes of black smoke, right in your face. I developed a sore throat just two days in, despite the constant 90-degree weather, to which I directly attributed to the higher than normal amounts of pollution consumption. It’s time like these that make me appreciate the emission regulations aimed at protecting my delicate, delicate lungs – despite many a previous complaints any time car inspection time rolled around.

A please scene, but detrimental to your long-term health

But really, who can resist these iconic photos (and I’m not even a car guy)

6. Life can be extremely cheap

Prices can be extremely, extremely, super extremely cheap, especially when paying in moneda. Covered seats at a baseball game run for 4 cents, while cheap seats in the sun are half that. Ice cream at state-run institutions costs you seven scoops for 20 cents (a limit of two orders). Ubiquitous personal pizzas are as little as 20 cents. A 4-hour ride on local ‘camion’ transport came to a dollar. When items are this subsidized, perhaps $25 a month isn’t so bad after all (entertainment – the theater, baseball games, ice cream, etc. – in particular is very cheap, perhaps a means to keep the masses occupied).

Paid double for this view!

7. The lack of supplies is real (albeit exaggerated)

One aspect of life often assumed about living in a communist economy, is the dearth of supplies considered to be basic elsewhere. This was apparent right from the start, when checking in for the flight at the airport, you could easily spot who was Cuban and who was not based on their luggage. All sorts of modern appliances, from air conditions to flat screen TVs, from tires to diapers, were brought onboard.

That tire will find a good home

The emphasis on bringing such goods underlines how common shortages can be – not just of appliances but also food items. For example, a casa owner in Vinales went to a neighboring town, the capital of the region, on a daylong search for a simple bathroom mirror, only to return empty-handed. A renowned restaurant was out of milk, beef, and pasta the night I dined there, rendering 80% of its menu obsolete – and no one else batted an eye. Another lady explained that she assumes her Argentine boyfriend, who regularly visits the island, could never live in Cuba because how could he “go from a place that has everything, to here?”

The issue is compound by the ‘space ratio’ in stores – that is unnecessarily large structures filled with a small amount of goods. If the mid-size store downsized instead to that of a local tienda, its shelves would be appropriately filled with enough goods to fill its space. But when you have unnecessarily large stores with vast aisles and little to put in them, the visual effect is magnified (perhaps a consequence of cheap state-regulated commercial space rent?).

A semi-stocked pharmacy

Adaptation to this aspect has engendered a mentality of ‘buy as much of everything that you can, when you can.’ During ‘egg day’ in one small town, everyone walked away from with at least five dozen – not a single person bought just two or three for that evening’s meal. The state attempts to counter this mentality with general person limits on how much of a certain item can be bought at a time, but as seen above, people know how to get around the rules.

The shortages mean that creative resilience of the population to obtain goods manifests itself in the most unexpected of ways – when calling down to the reception of a hotel in Havana for a completely unrelated issue, the polite, young receptionist closed the conversation with “are you selling anything? The Mexicans that stay here sell things, and we will buy them!” Emphasis on the lack of specificity must be noted here, as literally “anything” would be up for discussion. I was half-tempted to turn my entire duffel bag into a quick economic experiment to gauge the demand for goods such as tattered socks, used razor blades, and dried out pens, but spared everyone the indignity of rustling through my dirty underwear in the hopes of finding a new dinosaur shirt.

However, it doesn’t seem as bad as it could be – you can find toilet paper at least. The prior insistence by many to bring my own soap also proved to be unnecessary (mainly because I rarely showered, personal choice).

What’s available today (sugar, salt, rum, beer, and rice – the essentials)

8. An entire ‘line culture’ exists

Another interesting facet of life in a communist system often portrayed in the media, is presence of long lines for everything. Cuba is no exception to this, and lines of people waiting to conduct simple tasks such as buying bread, changing money, or even buying ice cream are commonplace. So common in fact, that it has resulted in the development of an entire culture of line waiting.

Generally guards limit the number of people actually allowed inside the institutions, meaning that a crowd of people manifests on the streets outside. While it may appear chaotic, it is anything but. Everyone is aware their place in line, as any newcomers must ask “el ultimo?” (i.e. the last?) and get behind that person. Often, however, people don’t physically wait in that spot, but maintain a general reference to their place in the order, while line neighbors will save the spots of those who smartly multitask by leaving to do something else as the line slowly progresses. Despite the fact that people are standing everywhere, order is highly respected, and you will not be cut. While this courteous line culture is nice, on the other hand it indicates just how used to waiting in line people are, and how much of one’s daily errands are consumed by such a process. Rarely did I come across someone who was surprised that, when he went to his local tienda to buy milk, he would have to wait what I consider an excessive amount to complete the transaction.

No one cutting in this line for Internet

9. Advertising comes in the form of revolutionary propaganda

Flipping through newspapers or watching TV, I was struck by the limited advertising. The 3.5 minute commercial breaks I take for granted were refreshingly absent. Revolutionary marketing, however, is big business. Photos and quotes from Fidel, Che, Raul, and even the occasional Huge Chavez are everywhere, such as Fidel’s anti-capitalist tirade inside one of Havana’s more X-mas decorated malls. A different sort of take on advertising, but I suppose the end goal is similar – having you buy into a system rather than buy a product.

10. People are educated & highly aware of the world outside their island home

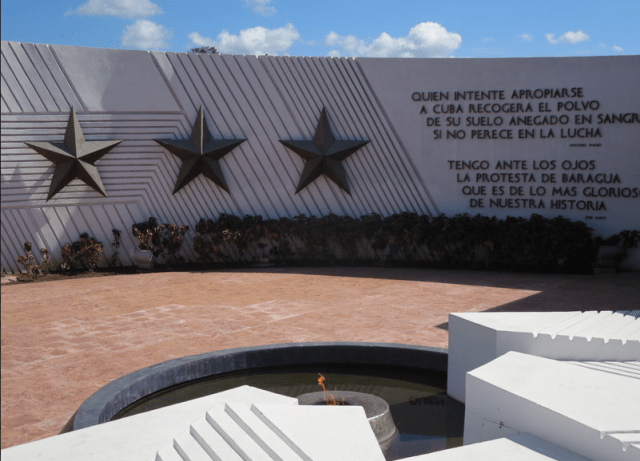

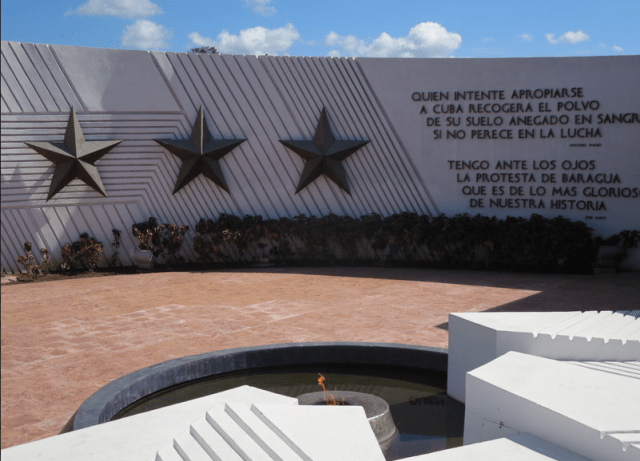

I encountered a highly educated populace, albeit it the embedded effects of the revolutionary advertising are impossible to wash away completely (for example, monuments to the five ‘antiterrorist’ Cuban spies exchanged in 2014 for USAID contractor Alan Gross, as part of normalizing relations with the United States, were everywhere, and everyone could name all five members). Nonetheless, most Cubans cited the power the US Congress holds over the restoration of full relations, an awareness of local politics in another country that I couldn’t assume could be true on the reverse. As one casa owner put it, “everyone here knows about politics – and if you don’t, you’re a pile of yams.” I couldn’t have agreed more, and serves as an indication of the high human capital potential often discussed when it comes to the future of Cuba.

11. Despite the lack of universal technology (i.e. the Internet), things work – just a bit differently

Cuba works, just differently at times. Internet has been gaining traction recently, as the government has established public Wi-Fi spots at the main parks in most cities. You buy a pre-paid Internet card, log-in with your device, and are good to surf the surprisingly decent connections. Private connections remain a rarity due to high costs (though this is changing), as do cyber cafes, but you can always know where a Wi-Fi spot is by the huddled masses of (largely) young folk holding phones, tablets, and laptops (another recent development, given that ownership of such items was banned until 2008).

Internet is truly a communal affair in Cuba!

The lack of technology is apparent in other areas, as many businesses rely on old school models. Reservations for buses, taxis, and even flights came down solely to having a name on the right piece of paper. After my flight out (on the state-run airline) was randomly canceled a week prior unbeknownst to me, and I had to wait a day for the next one, the manager simply wrote my name down and told me to come back tomorrow. I protested, assuming there had to be some electronic input to this process, or that some sort of confirmation receipt should be issued to me, especially as this particular manager wouldn’t be there the next morning. As he shooed me away, I was certain the next day would be a repeat situation and I would half to make a new life in the Havana airport a la The Terminal– style. But the paper made its way to the right people, and the next morning I checked in without a hitch on a different flight than the ticket I presented. Perhaps that’s how things used to work before the Internet took over – I don’t really remember, and soon no one else outside of Cuba will either.

12. The simplest of things we take for granted are not always easy

Even just trying to accomplish basic tasks can be frustrating. I went into a store that looked like it was decently stocked to buy orange juice (an attempted ailment against the pollution induced-sore throats mentioned above), and was pleasantly surprised to see that they had an imported brand from Spain (thus avoiding the angry and bitter Cuban citrus – also just finding orange juice in itself was a bit of an accomplishment, based on previous lengthy and unsuccessful searches). I grabbed one and went to the counter, where a lady with an open cash register was separating the moneda from the CUC in the drawer. A guy is standing next to her, typing numbers into a small machine while yelling other numbers out to seemingly no one in particular. This goes on for at least five minutes, as she never looks up. Finally she tells me I have to go to the other side of the store, something that apparently couldn’t have been said before. I go to the other side where the previous number yelling guy is now ringing up people. I wait in line for a few minutes, then he quizzically looks at me and remarks “oh, you brought your stuff over here?” Confused by that statement, I look back to the other side of the store, and the counting lady who rejected me, is now ringing up customers! No matter, I decide I really don’t want to ever do this again, so I quickly grab a second juice to not avoiding having to return (picking up that Cuban mentality quickly). While coming back to the line, I noticed another lady has locked the store entrance, even though its only 4:45 and they advertise a closing time of 5pm. Some customers try to push the door open, but she holds them back and explains that they need to close early to clean up some water. I look over to where she is pointing and see a huge puddle of expanding dirty water – apparently one of their meat freezers broke and was rapidly flooding the entire store. The whole process was emblematic of how the simplest things sometimes are not so – all I wanted to do was buy orange juice, and now nearly thirty minutes later I was in danger of having raw-meat water seep into my shoes. Times like these I appreciate the uneventful, albeit impersonal, routine 7-11 interactions that ensure I can acquire a product without losing half a day (or a sock).

13. There is a strong sense of community

One of the ‘soft’ effects of communism many sympathizers argue is the heightened sense of community, especially with the supposed universal state-imposed equality. In Cuba, this can be apparent through the lack of major crime, especially compared to some of its neighbors in the Caribbean and Latin America (one of the most violent and murderous areas of the world). But I witnessed this at other, more minor yet just as revealing, levels. Taxis asking for directions in neighborhoods they were unfamiliar never failed to get an adequate response – often the first person stopped would be just as unaware, but they would in turn start tracking down others on the street until a firm answer emerged. No one walked away before the taxi request was fulfilled – rather there was a sense that despite not knowing one another and just meeting, we were all in this together.

Impromtu community street dance party

14. And finally – all the idiosyncrasies are what make Cuba unique, and hopefully merit even further future exploration!

Until next time . . .